To Err is Human: What are Type I and II Errors?

As much as researchers, journals, and newspapers might like to think otherwise, statistics is definitely not a fool-proof science. Statistics is a game of probability, and we can never know for certain whether our statistical conclusions are correct. Whenever there is uncertainty, there is the possibility of making an error. In statistics, there are two types of statistical conclusion errors possible when you are testing hypotheses: Type I and Type II.

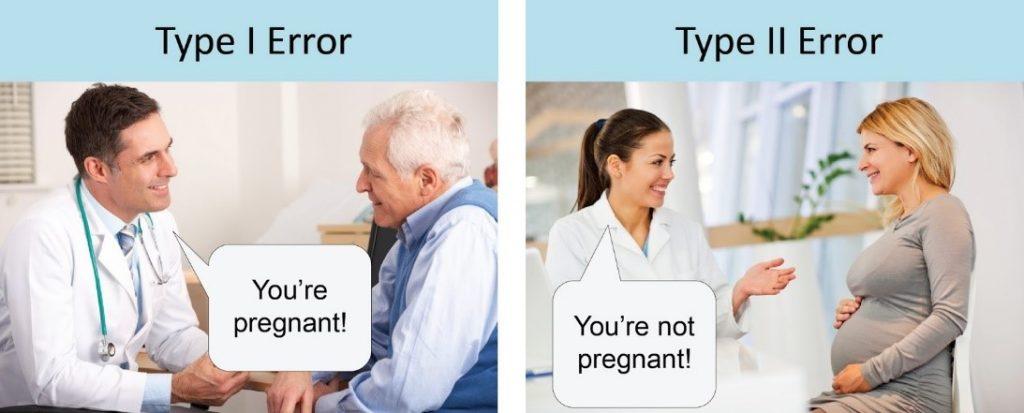

Type I error occurs when you incorrectly reject a true null hypothesis. If you got tripped up on that definition, do not worry—a shorthand way to remember just what the heck that means is that a Type I error is a “false positive.” In this study, you compared happiness levels between people who held a puppy and those who merely looked at one. Your null hypotheses would be that there is no statistically significant difference in happiness levels between those who held and those who looked at a puppy.

However, suppose there is no difference in happiness between groups. It means people are equally happy holding or looking at a puppy. If your statistical test was significant, you would have committed a Type I error, as the null hypothesis is true. In other words, you found a significant result merely due to chance.

The flipside of this issue is committing a Type II error: failing to reject a false null hypothesis. This would be a “false negative.” In the puppy example, suppose you found no difference, but people who hold puppies are much happier. If your statistical test was significant, you would have committed a Type I error, as the null hypothesis is true.

Image source: unbiasedresearch.blogspot.com

The chances of committing these two types of errors are inversely proportional—that is, decreasing Type I error rate increases Type II error rate, and vice versa. Your risk of committing a Type I error is represented by your alpha level (the p value below which you reject the null hypothesis). The commonly accepted α = .05 means that you will incorrectly reject the null hypothesis approximately 5% of the time. To decrease your chance of committing a Type I error, simply make your alpha (p) value more stringent. Chances of committing a Type II error are related to your analyses’ statistical power. To reduce Type II error, increase power by boosting sample size or relaxing the alpha level.

Depending on your field and your specific study, one type of error may be costlier than the other. Suppose you conducted a study looking at whether a plant derivative could prevent deaths from certain cancers. If you falsely concluded that it could not prevent cancer-related deaths when it really could (Type II), you could potentially cost people their lives! If comparing happiness levels between holding and looking at a puppy, either error may not be crucial.

If you’re like others, you’ve invested a lot of time and money developing your dissertation or project research. Finish strong by learning how our dissertation specialists support your efforts to cross the finish line.